I recently taken part in a game jam hosted by Opera for their GX Games platform using Game Maker. I had 2 weeks to make a game that fit the theme of predictably unpredictable. The game I ended up making is a text adventure game with turn based combat and lots of randomised elements, you can play it here. Below I’ve given a high level overview of how I made it.

At the start of the jam I spent the first 24 hours just thinking of ideas that I could make within the time frame. Some of my first ideas included a vampire survivor or rogue like game where the weapons and abilities would have randomised effects. This could include a weapon that would fire randomised projectiles that would range from high damage missiles to spitting out eggs that just splat on the floor. I felt like these ideas were more obvious and would likely be something other people would be making. Eventually I landed on the idea of doing a retro text based adventure game with turn based combat. The reasoning for this being that it meant I could keep the graphics down to a minimum and try to get as much content added as I could by writing small dialogue events with multiple choices (which turned out to be more ambitious than I realised). For the visual style I wanted it to have a retro pixel art look, keeping the number of colours to a minimum and the resolution low. I was aiming for something between Loop Hero, Heroes of Might and Magic, and old MUD text games.

1st Stage: Rendering and Proc Gen

The first tasks I focused on once I started development was to build both the graphics system and the procedural generation for the map. Both of these tasks eaten into a lot of my available time which I wasn’t expecting but I was still able to get this done in a few days.

// World Ground

var groundLayer = new RenderLayer( eRenderLayer.world_ground, renderWidth, renderHeight, false );

groundLayer.CreateNewCamera( 0, 0 );

groundLayer.clearAlpha = 1; // Set to opaque as it's the first surface to be drawn.

array_insert( layersArray, groundLayer.layerIndex, groundLayer );

// World

var worldLayer = new RenderLayer( eRenderLayer.world, renderWidth, renderHeight, false );

worldLayer.CopyCameraFromLayer( groundLayer );

worldLayer.clearAlpha = 0; // Transparent to see ground objects underneath.

array_insert( layersArray, worldLayer.layerIndex, worldLayer );

// UI

var uiLayer = new RenderLayer( eRenderLayer.ui, renderWidth, renderHeight, false );

uiLayer.CreateNewCamera( renderWidth * 0.5, renderHeight * 0.5 ); // Offset the position so that the top left corner is 0, 0.

uiLayer.clearAlpha = 0; // Needs to be transparents to see the game surface behind it.

array_insert( layersArray, uiLayer.layerIndex, uiLayer );

// App

var appLayer = new RenderLayer( eRenderLayer.app, applicationWidth, applicationHeight, true ); // Set width and height to the application size as it needs to match the screen size.

appLayer.CreateNewCamera( applicationWidth * 0.5, applicationHeight * 0.5 ); // Offset the position so that the top left corner is 0, 0.

appLayer.clearAlpha = 1; // Set as opaque as all other surfaces are drawn to this one after being cleared.

array_insert( layersArray, appLayer.layerIndex, appLayer );

Since this was made in Game Maker the graphics rendering is already handled for you for the most part but being a pixel art game I wanted to make sure that the game rendered in a low resolution. This meant building some custom rendering steps set to a low resolution, and then scaling it all up to the output resolution using point sampling. This can be done in Game Maker using surfaces which act like render targets, you can then associate a surface with a specific view and camera. In the end I had several of these surfaces so that I could control the way the game rendered (shown in the above code snippet). I used one layer to draw the ground objects, another for the world objects, one for the GUI layer, and finally a copy or app surface used to draw all of the other surfaces to in the correct order which also allowed me to apply custom shaders before presenting the result to the application surface, similar to presenting to the foreground buffer in DirectX.

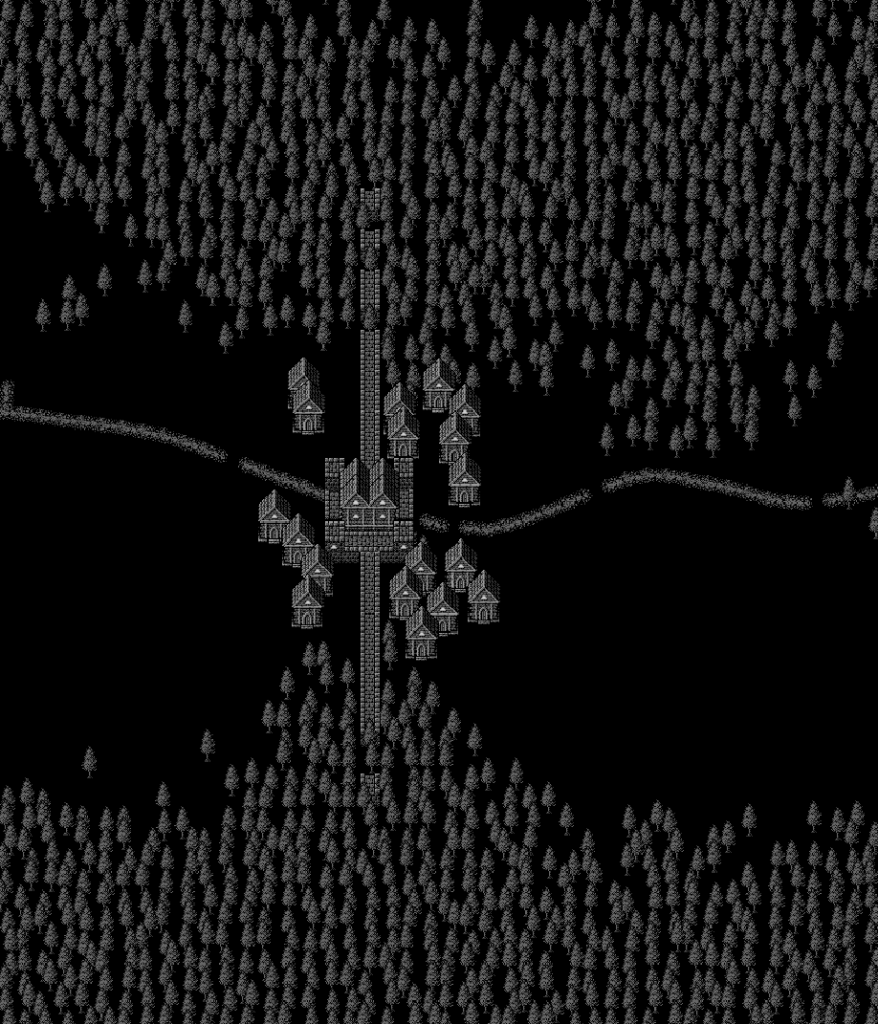

For the game itself I first focused on the environment, or the map. I wanted each run of the game to be different helping to fit into the theme of being unpredictable. It taken a good chunk of the time to build but I managed to build something that worked for the story I had in mind. The generation algorithm used a 2D grid to assign values to each cell. A single cell would be given a type and a context value that was used for different things depending on the cell type. The algorithm first finds a start and end point, these would be randomly placed on the left and right edges of the grid. It then draws a path between these two points. The path was constructed using a modified version of Bresenham’s line drawing algorithm but instead of aiming directly for the target it had a randomised offset direction that changed at randomised intervals resulting in a wavy path. The rest of the elements were then placed in relation to the path and the end and start points. Houses and castle walls were placed at the start and end of the path, and the treeline was placed a randomised distance from the path with it pinching in at the end and start points to help guide the player. Finally the game POI events were placed along the path, again using randomised distances, these are points in the world that will trigger specific events when overlapping with the player sprite.

Using a grid system like this can result in objects being placed unnaturally especially when there is a high density of the same type of objects. One big problem I came across was that the tree line had a very solid edge which didn’t look like a natural forest. To fix this I used a box blur algorithm on the tree cells to spread the cells out and give it a more natural look. Each tree cell had a value that represented the density of the trees in that location and it’s these values that would be effectively blurred to create a forest that had a softer edge where the density would falloff.

Once all the cells had been given a type and the treeline was blurred the final step was to loop through the grid and place instances of the relevant objects in that location. This stage also included some randomised elements especially for trees which had some offsets applied to avoid all the trees being placed in a perfect grid pattern. The density of the tree cell also acted as a percentage chance that a tree would be placed in that cell. Where the tree cell had a lower density it was much less likely to spawn a tree in that location.

2nd Stage: Gameplay

Onto gameplay. I needed a way to move a character through the map. I decided that it would fit the style of game better to have it be played entirely using the mouse, which meant player movement would need to be point and click. This required implementing the A* pathing algorithm to allow for movement through the map while avoiding obstacles. This is a well known algorithm so I won’t describe it in detail here but basically it attempts to find the most optimal route from point A to point B while avoiding dead ends. Because the player could point the mouse outside of the pathable area I also had to add in a way for the algorithm to exit early if it searched a maximum number of cells and return a close enough result.

I did come across an issue with the way I had built the world that was causing the performance to drop. Having so many object instances in the world was the main cause of the issue. To get around this I only spawn tree instances long enough to generate the pathfinding grid, after that the trees aren’t really needed as they are just a visual element. The proc gen spawns in all the trees as instances, this allows the pathing system to use the collision area of the instances to figure out which cells can be pathed to and which can’t, once that’s done I then loop through all of the tree instances in the room, store their position in an array before deleting all the instances. The game then draws a tree sprite at all the cached positions every draw call. Doing this made a big improvement to the game’s performance as there was no longer such a high number of object instances in the room processing the step events, draw events, updating collisions, etc. Replacing that with just sprite calls was much faster.

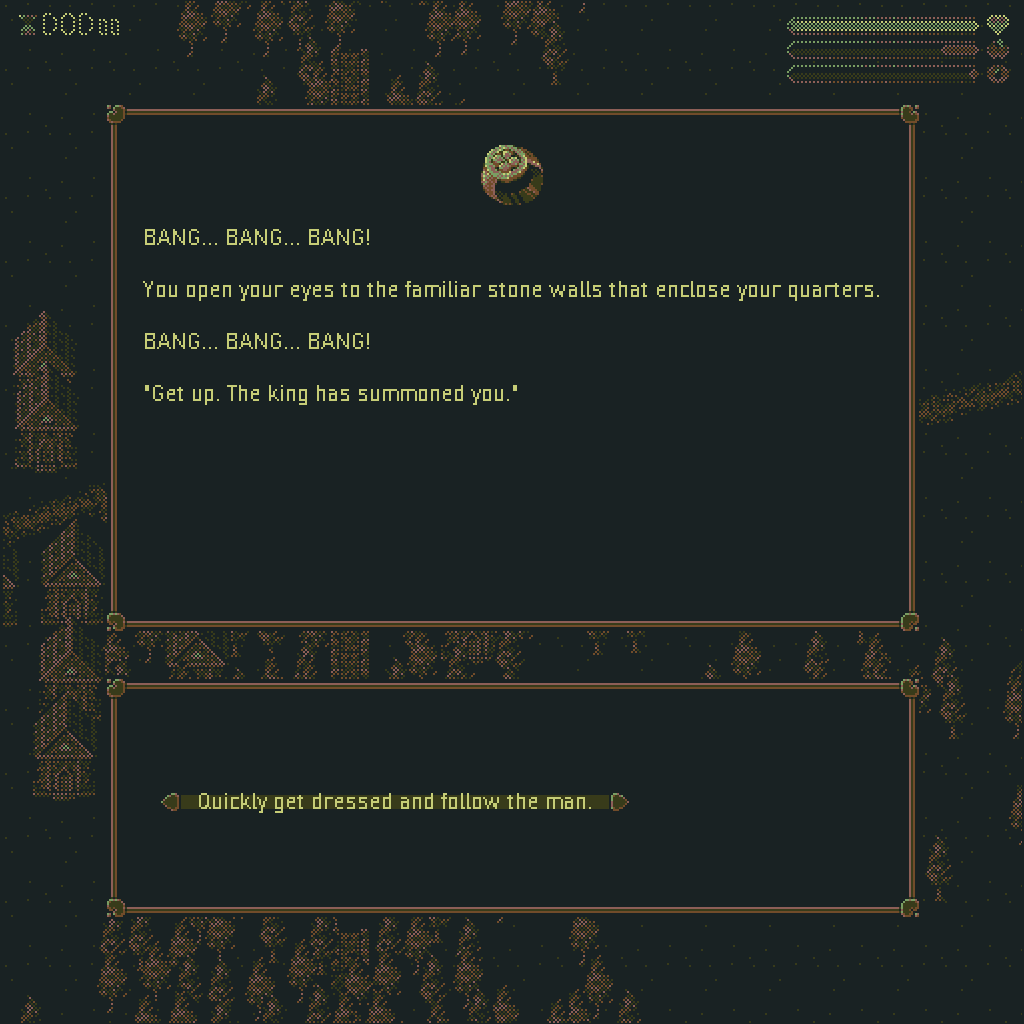

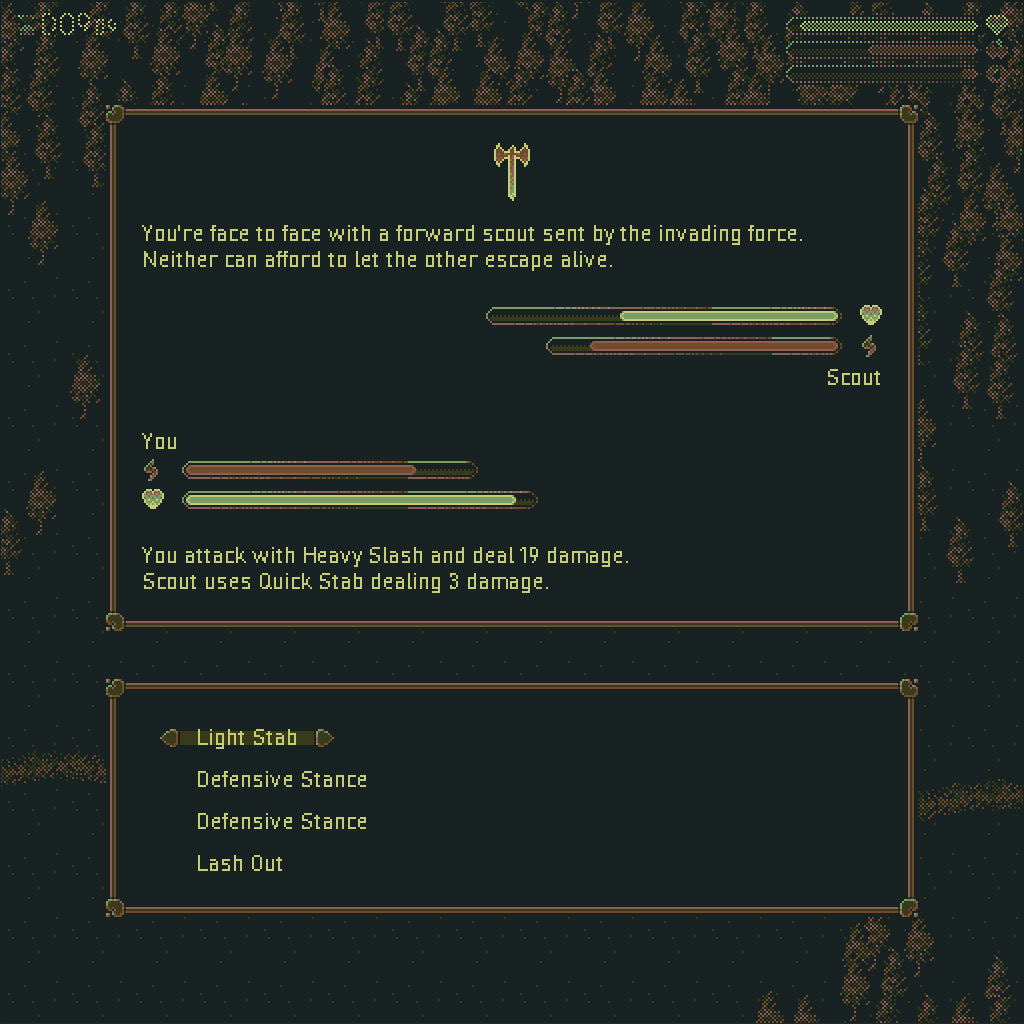

The main gameplay is delivered through two methods a dialogue system and a combat system. Since both were text based it allowed me to build a single system that could handle both with some variations between the two. The dialogue events just had to display some text describing what was happening along with up to 4 options for the player to select. The combat worked in a similar way except instead of progressing step by step through a story it would instead describe your opponent, show you some UI elements for health etc, and then give you up to 4 choices for attack moves that could be selected. Both of these were designed to fit the theme of the jam as the outcome of the stories were hard to predict given that players could make different choices and some of the choices had randomised outcomes. The battle system also randomised the available moves the player could choose from after every turn so you could never quite predict how the combat would play out and you would not be able to just pick the same strong move over and over.

function DialogueEvent_MushroomMystery_A() : DialogueEventData() constructor

{

displayString = "With little thought for the potential dangers involved in eating unidentified mushrooms you grab one at random, yank it out of the ground and stuff it in your mouth. " +

"You can feel the residue mud grinding between your teeth as you chomp down.";

optionStrings =

[

"Spit the mushroom out.",

"Continue to ingest the mushroom.",

];

OptionA = function(){ return new DialogueEvent_MushroomMystery_AA(); }

OptionB = function()

{

var percent = random( 1 );

if ( percent <= 0.1 ) return new DialogueEvent_MushroomMystery_AA();

else if ( percent <= 0.4 ) return new DialogueEvent_MushroomMystery_BAA();

else if ( percent <= 0.7 ) return new DialogueEvent_MushroomMystery_BBA();

else if ( percent <= 1.0 ) return new DialogueEvent_MushroomMystery_BCA();

return new DialogueEvent_MushroomMystery_AA();

}

}

The system that made this work was all data driven which allowed me to quickly add in new dialogue or combat events simply by creating a struct and filling in some of the relevant data. These structs would be passed to the event system which would use that data to construct the UI for the event as well as handling the dialogue outcomes and the results of each move during combat where player’s and enemies’ health etc could be reduced or increased. With Game Maker not having a native way of handling branching data sets I simply relied on having a long list of structs using a labelling system that appended a letter representing the options that would lead to that story point. In a larger long term project this would be a horribly error prone way of handling branching dialogue but for a small game jam it was a very efficient solution.

One major thing to note about the gameplay is that the player had a stress level. This further aligned the game with the jam theme. As the stress level increased, which could be caused be receiving negative effects, the game became more unpredictable. Dialogue events were more likely to give negative outcomes and during combat you had a chance to fumble your attacks based on your level of stress. It also made it more possible to get creepier or weirder events pop up like a ghost version of the player or an evil rabbit. A big part of the strategy to beating the game is to manage your stress levels by learning which dialogue choices lead to positive results and how to minimise the damage you receive during combat.

OptionA = function()

{

_g.playerChar.ChangeStat( ePlayerStat.hunger, eStatChange.medium, eChangeType.punishment );

_g.playerChar.ChangeStat( ePlayerStat.vigour, eStatChange.medium, eChangeType.punishment );

_g.gameManager.daysPassed += 0.5;

return INVALID;

}

Last thing to talk about in terms of gameplay was the way I managed stat changes for the player. I knew the game would require some balancing to ensure that beating it was challenging but not impossible. What I was keen to avoid was wasting a lot of time tweaking lots of different numbers that were spread out throughout the code base where a reward was given for one dialogue option or the player’s stress was increased during combat, and so on. If I needed to alter the difficulty a bit I didn’t want to be having to do this in a lot of places in order to keep it consistent. To avoid this I created a system where the player’s stats were changed through a single function. This function accepted 3 arguments all enums, the stat type (health, food, or stress), the amount to change by (small, medium, or large), and if it was a reward or a punishment. By using enums like this instead of hardcoded values I could then have all stat changes use predefined values for each amount. This meant that if I needed to heal the player a small amount I only needed to call this function with the enums for health, small, reward. The values I used were also further tweaked by the global difficulty setting, so depending on the stat and if it was a reward or a punishment the stat change value was either scaled by the difficulty multiplier or by its inverse. By building a system like this I was then able to rebalance the whole game by changing only a very small set of numbers.

3rd Stage: Finishing Touches

The last two finishing touches I had time to do just before submission was to add audio and to create a LUT shader. For the sound effects and music I used packs I purchased from Ovani Sound. It was a simple job of finding some packs that fit my game’s style and then drop them in. Game Maker very much handles audio for you, all you have to do is tell it when you want to play which audio files. I added some additional code on top of this to automatically apply a small amount of randomised pitch and gain so that repeating sound effects didn’t sound exactly the same. I also added in some safe guards against playing the same sound file multiple times at the same time or too closely together.

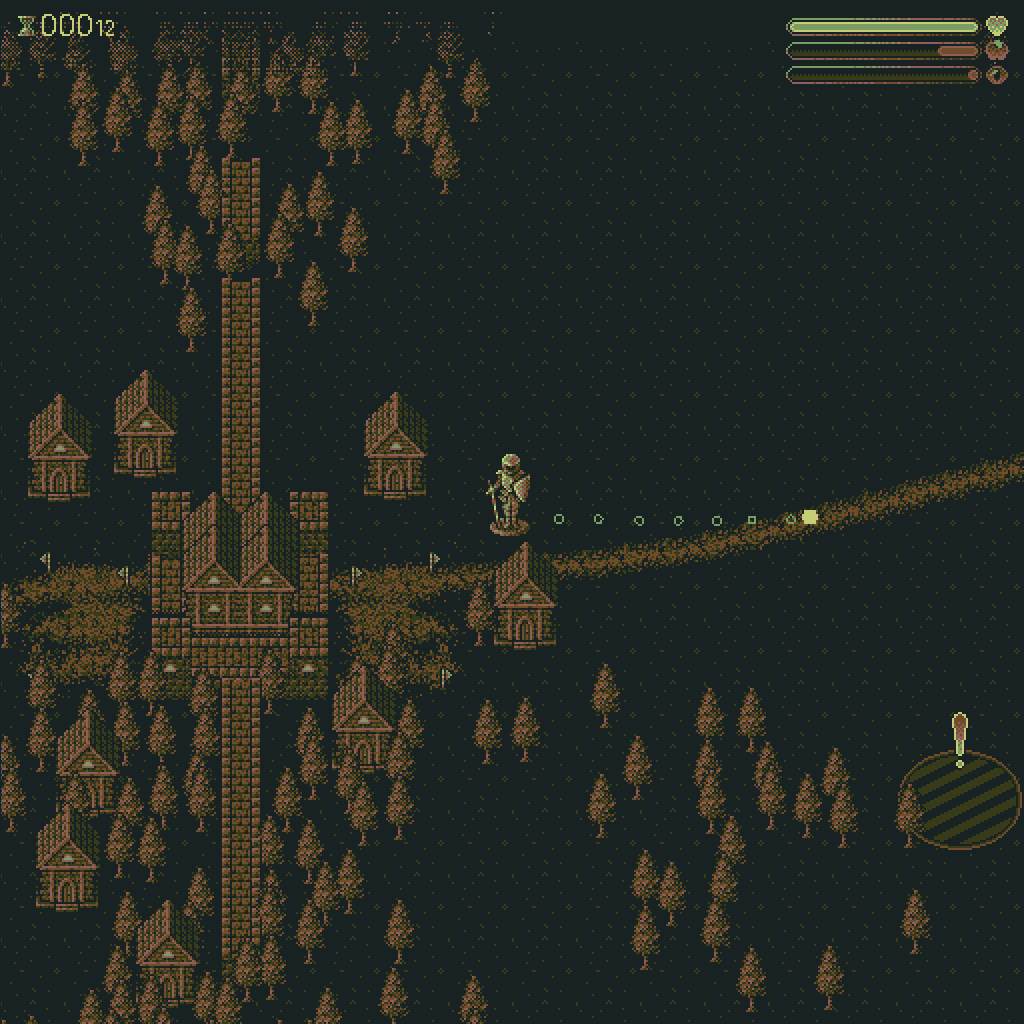

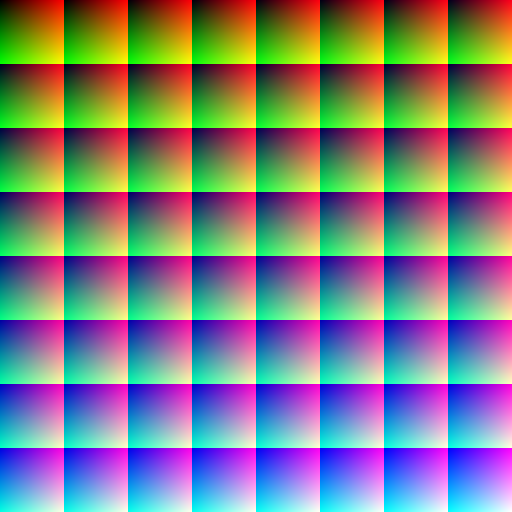

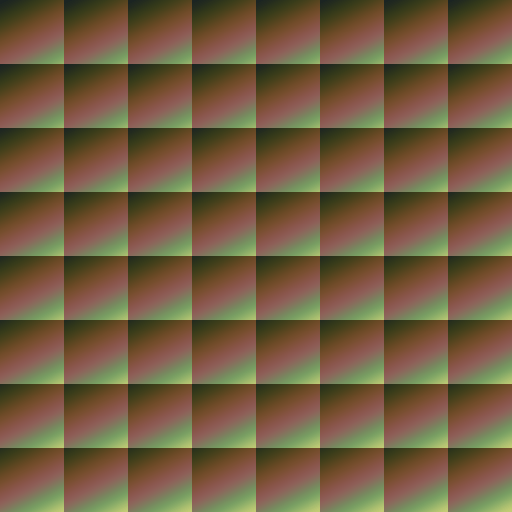

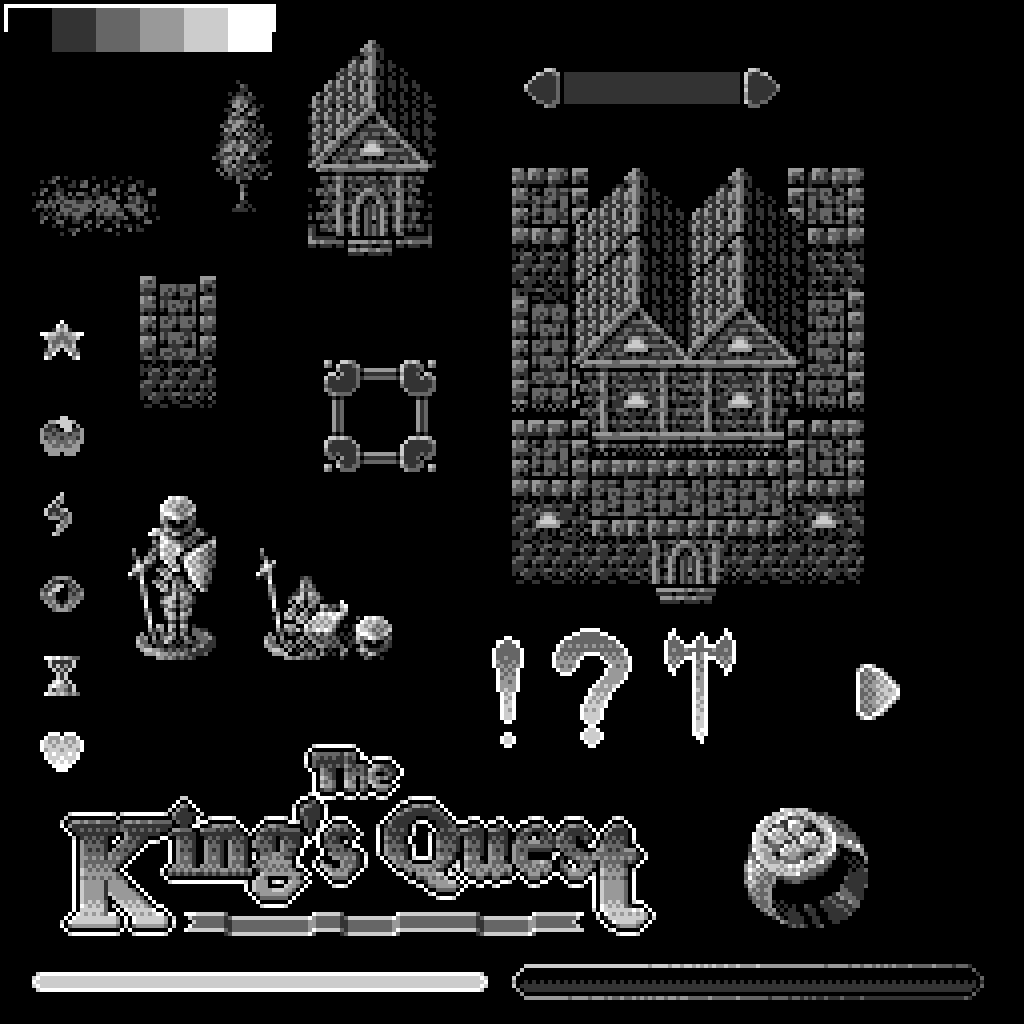

The LUT shader was something I absolutely wanted to make time for. All the sprites I made for the game were made in black and white, or more accurately using 6 shades of grey including white and black. This created its own unique aesthetic but I never intended to display the sprites that way. Instead I wanted to use the grey as a sort of index for a palletised colour. The ultimate goal with this was to make it easy to then change the colours of the game to fit the mood (unfortunately I didn’t have enough time to make full use of this but I was at least able to change the final colour palette). This is where the colour look up table shader is needed or LUT shader for short. With this kind of shader the input colour from textures are not outputted directly but are instead used to index into another texture where the final output colour is found. The default unaltered version of this looks like a colour picker that you see in pretty much every art and graphics tool where the output colour matches the input colour but the altered LUT changes those colours to produce either subtle colour changes or change them completely. Not only was I able to use this to change the final colour palette of the game without having to change the sprites but I also used it to create a flashing effect for when the player triggers a dialogue or combat event similar to the way the old Pokémon games would flash or invert the colours a few times before transitioning to the combat screen.

Final Thoughts

Voting is still on going so I’m yet to find out how I’ve done but I’ll update this post once I do, you can see all the other submitted games here. Overall I’m happy that I managed to get something finished and mostly bug free. That on its own is hard enough to do during a game jam. I’ve done a good few of them now and most of them have been a buggy mess but the more you do the better you get at estimating what you can build in the time given.

I would have liked to have gotten more dialogue and combat events in, it doesn’t take long to see the same events over and over but creating branching storylines even small simple ones can take a bit of time to write. Especially when you’re not a writer.

When it comes to the theme I think I’ve created something that is unpredictable in several ways but I also think some of my earlier ideas may have resulted in a game that fit the theme better, that would have also been more fun to play with a broader appeal.

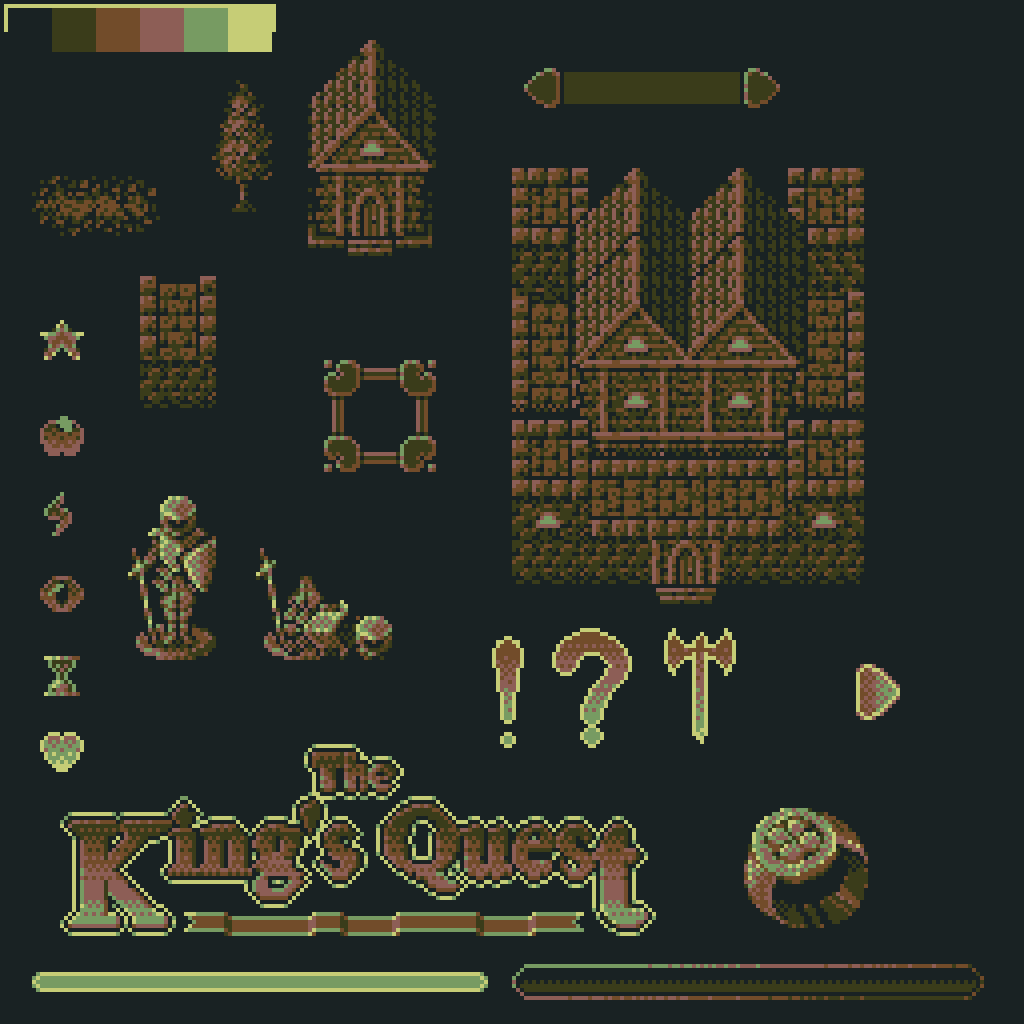

One of the things I’m most happy with is the look of the game. It may not be bright and colourful or immediately eye catching but I like the colour palette. I think it captures that retro pixel art feel really well and some of the sprites I’m really happy with. The ones I think look the best are the title text, some of the UI elements, and the character sprite. For the character I wanted it to look like a figurine being moved across a map rather than a person walking through the world. This allowed me to visually explain away the lack of animations while still creating something graphically interesting. I do think the first few sprites I did, like the buildings, don’t look as good as the later ones once I figured out a style that I was happier with.

I had a lot of fun taking part in this game jam and I think in the end I managed to submit something that’s not too bad given the time frame. If you’re interested in giving my game a try you can play it here.

Leave a comment